‘To do nothing at all is the most difficult thing in the world.’- Oscar Wilde.

On April 1st, I crushed and broke a fingertip (it wasn’t a car door injury, but a bit like that), and had to take three weeks off work.

Minus the codeine, antibiotics and throbbing, you might think a few weeks of sitting on the couch watching films and reading books doesn’t sound like such a bad thing.

Yet, I was by and large pretty miserable, and had all the time in the world to wallow in it which turned out to be very unhelpful.

Fortunately for me, I work with Psychologists, so, when I began to feel a bit brighter, I figured I would give some of their advice a crack.

Here it is – my experience of short-term, situational depression, climbing out of it, and how you can apply what I learned to you and your team.

Hopefully you don’t need to break any bones to find the same eureka moments.

For anyone who is interested in this kind of thing - that wee squashed mushroom cloud is an X-ray on the end of my finger.

To deal with ‘right now’: Take 5

This is advice traditionally for anxiety that I have tweaked to apply to depressive episodes, since the concept is easy to remember and it works for me.

Stop, and think of something you can taste, smell, touch, see and hear. This has the effect of breaking you out of unhelpful, repeating thought patterns and bringing you into the present moment.

Coping strategies (once you are ok ‘right now’ and need to deal with the next few hours/days:

Nobody is happy all of the time.

We all experience a range of emotions over our lifetimes. This could be a short-term dip in mood, or it could progress into something more serious.

Knowing this, it can be helpful to be aware of your triggers and coping strategies for when negative thoughts arise, if those thoughts continue to the point that they are unhelpful or impacting your life.

In the past, when I’ve been susceptible to stronger bouts of depression, I’ve had a list of strategies written down and kept in a drawer so I don’t even need to think about what to do – I just get the list out and tick them off.

For me, anything sensory works. My first port of call is a walk, listening to music. Other options: taking a bath, a cold-water swim, calling one of a few friends who I know are always there and always make me feel good. I draw, I read poetry, I watch feel good films.

I start by asking myself ‘what worked last time’ and then I do that.

Mind UK has a great list that you could try as a starting point: https://www.mind.org.uk/need-urgent-help/what-can-i-do-to-help-myself-cope/relaxing-and-calming-exercises/

Obviously, this is a joke, but I do find colouring helpful and there’s a range of colouring books available for adults including ‘sweary’ versions that can be very cathartic if you’re a fan of the F word.

The Gibbs Reflective Model

When you’re in a better place, it can be helpful to reflect.

Reflecting on what happened, why it happened, and what you will do next time can at the very least give you the confidence that when a blue mood strikes, you have tools in your toolbox ready to handle it.

To be honest, I didn’t formally work through all these steps. I just approached my thoughts and feelings with a bit of curiousity, when I felt able to reflect without anxiety or self-blame.

One of the things I noticed is that I’d got a bit caught up in a ‘worry cycle’ - both about the immediate impact of the injury itself and second, about why ‘not working’ had thrown me so much.

Image taken from: https://www.ed.ac.uk/reflection/reflectors-toolkit/reflecting-on-experience/gibbs-reflective-cycle

The Worry Cycle

This is what happens when you get stuck in a ‘thought loop’ – it could be a mild fear about possible future outcomes, or full-blown anxiety.

For me it looked like this: my finger is broken, I don’t know when it will get better, I can’t do the parts of my job or hobbies I like best, this will make me depressed, what if I can never do my job again, I will be miserable and broke, what if I can't pay my bills or do the things I enjoy; and round and round and round again in an escalating thought cycle of ‘what ifs’.

There’s a couple of ways to get yourself out of a negative thought loop.

The first step is to be aware of the thought.

Another option is to play the thought through to completion.

For example:

‘okay, I am noticing that I am thinking I am worried about how long my finger will take to heal.’

It's okay to be worried. I’m experiencing a negative situation and this feeling is normal.

What is the absolute worst-case scenario? What are the chances of that happening? What steps do I have in place to prevent that happening?

I remember that I have experienced similar situations in the past and been okay in the end.

I can also try practising other thoughts:

‘this situation sucks right now, but I have managed difficult situations before and been okay. I can’t go kayaking, but I can walk in the park, I can go for lunch with my friends, I can read books that I enjoy. Soon I will be able to do other things too.’

Artist Credit: Owlturd

My second ‘worry cycle’ stemmed from worry about the worry itself.

Why did the absence of work make me feel so out of sorts? Am I some kind of broken workaholic?

I enjoy sitting at home watching Netflix. So why the hell was I so miserable about it?

Overthinking much, I know.

When the pandemic first struck the UK, I worked in recruitment. I took hundreds of calls every week from people who were on furlough and being paid to stay at home and who begged me to find them a key-worker job. People earning in the high five figures who wanted to swap their free time to do manual labour for minimum wage. People who told me that they would prefer to dig a ditch for no reason than be at home, idle, and living with uncertainty.

There’s layered reasons for this of course. Anxiety, worry, being in a capitalist culture, personal identity tied to profession, social connection, being in the midst of a global pandemic and all that fun 2020 – 2022 stuff.

Yep. It sucked.

Nonetheless, there seems to be something that we humans get out of work that satisfies us in some way which we don’t always find pleasurable in the moment (I am willing to bet that all of the people who phoned me didn’t always jump for joy on a Monday morning when their alarms signalled it was time to head for the office).

When I reflected on this, I became curious, and I turned to Google to find out what researchers say about happiness.

The first thing I discovered, is that according to Brad Pitt, ‘happiness is over-rated.’

What does he mean by this, and what else is there?

When I cast my mind back over my life, looking for moments of contentment and bliss, not a single memory was of work. Mostly, I was outside during these times, almost inevitably on holiday, and usually near water and with other people.

For a variety of reasons, (including my bank balance and the state of the rainforest), I can’t spend the rest of my life relying on finding happiness from moments spent hang-gliding over tropical islands. Therefore, if Brad Pitt has something more to serve up to me besides ‘happiness,’ I’m all over it.

I noticed that there’s plenty of things that don’t feel blissful while I’m doing them, but that give me satisfaction or meaning for one reason or another over the longer term.

Writing these blogs is a good example. The actual process can feel pretty torturous at times, yet, having completed a piece of writing that I am proud of – that says what I wanted to say – gives me a sense of satisfaction that I don’t get from anything else in life. Sometimes I hate it, but I wouldn’t give it up.

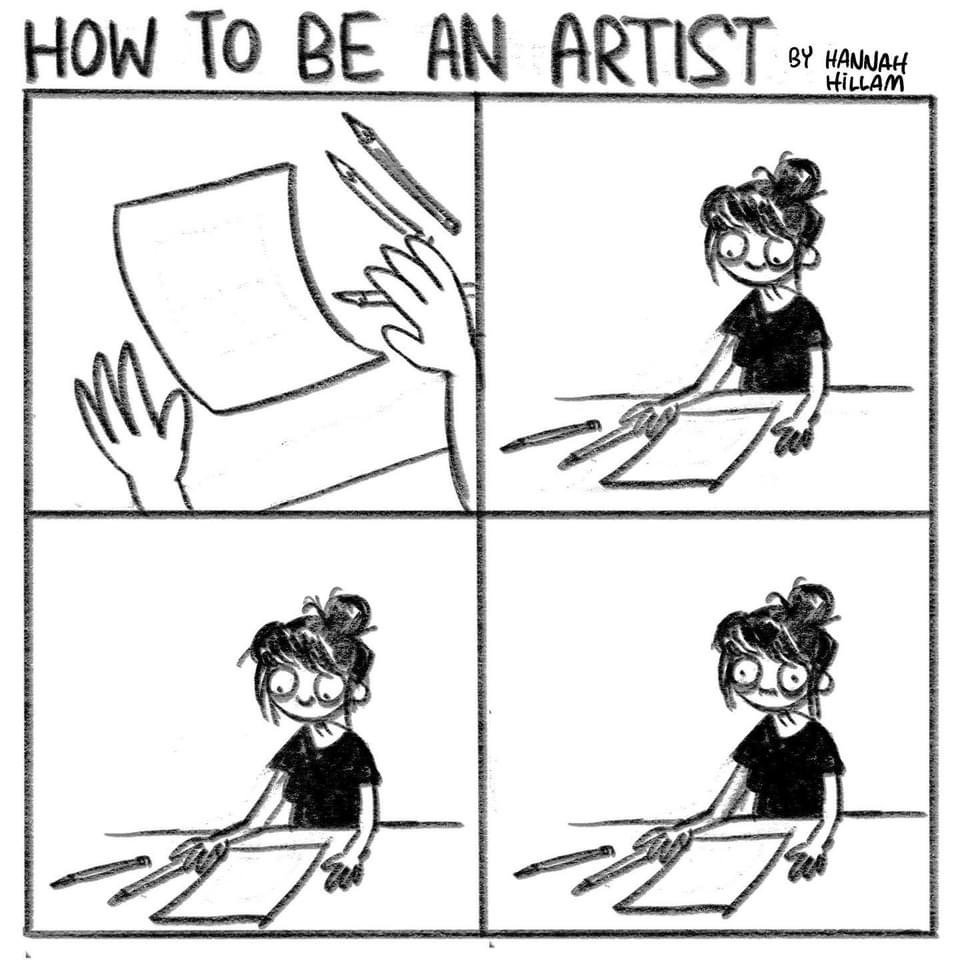

Artist credit: Hannah Hillam aka Verbal Vomit

Happiness is difficult to define, subjective, and associated with different value systems and personality traits. And, as I discovered from my recent finger-breaking experience, there seems to be a distinction between ‘in the moment’ happiness, ie pleasure, and activities that contribute to longer-term satisfaction and might include work.

We spend an awful lot of time working, so might it not make sense to strive for some kind of satisfaction, even if that isn’t served up in ways that feel immediately pleasurable?

Psychologists distinguish between hedonic happiness (moments of pleasure) vs eudaimonic happiness (experiences that give us meaning and purpose). Whilst over the course of human history, different individuals have championed one over the other, the generalised view is that both contribute to our wellbeing in different ways and are important for overall wellbeing.

Eudaimonic comes from the Greek word ‘Eu’ (good) and ‘Daimon’ (spriit). It means, essentially, striving to reach your purpose. Finding meaning in your life. See here for an excellent and interesting expansion on this idea: https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/what-doesnt-kill-us/201901/what-is-eudaimonic-happiness

This notion of wellbeing being made up of multiple components isn’t new. Consider how hedonic and eudaimonic happiness might fit into the Te Whare Tapa Whā model of hauora. My sense of wellbeing rises near water – this could fall into my sense of wairua, or spiritual connection; and my sense of connection into whānau.

My takeaways – it's okay to miss work, and feel a bit out of sorts without it (especially if this gap is unplanned).

Happiness comes from lots of different things. If, for some reason, something that makes you feel good isn’t doable right now, it doesn’t mean that you can’t find satisfaction or joy from something else. Us humans are adaptable creatures. We find happiness, meaning, purpose and contentment from all kinds of things.

Hang in there.

Artist credit: Chuckdrawsthings

Ideas for achieving hedonic and eudaimonic happiness

Hedonic

- Thinking about what makes you happy can be overwhelming, especially if you are feeling a bit blue. Instead, make a list of the experiences that give you pleasure.

- Try practising mindfulness. Pleasure is often associated with sensation. If something like a good meal, or diving into a cool river on a hot day gives you pleasure, then next time you do it, try to really extend the experience and pay attention to every moment.

- Plan more of these activities into your day, week, month and year. They don’t need to be ‘peak-level’ experiences. I might not be mounting-climbing in Rio De Janeiro any time soon, but I get a similar feeling from walking in the park across the street.

- If it floats your boat, have more sex. (I wasn’t going to throw this into an article for work, but hey, it’s a modern world).

Eudaimonic

Instead of thinking about what makes you ‘happy’ (in the commonly understood Western / pleasure concept of happiness) think about what gives you meaning and satisfaction.

Practise gratitude.

Give something back.

Practise mastery. Do your art. Don’t worry about being any good at it. The Aristolian idea is that living a life of purpose, and reaching your potential, is a continual exercise – a constant striving, not a finish line. The goal isn’t to be perfect but to keep doing the thing that you do.

Try to identify what puts you into ‘flow’ mode and do more of that.

If you are a leader, how can you help your team to find happiness at work?

For starters, and I hope this is obvious, don’t make them miserable. Ask yourself – are you a knob? Don’t be a knob. Treat people with respect and empathy, offer good working conditions.

Give people the time, and a sufficient wage, that enables pursuit of hedonic pleasure. For example – flexible working time to allow someone to attend an art class or go to their team footy practise.

Let them pursue Mastery – job crafting, autonomy, develop the skills that naturally draw them. Give people the opportunity to do more of the tasks that give them meaning.

Be aware of the danger signs – signals of low mood, or a more serious mental health issue, and the tools that can help.

Be aware of your own mental health and look after yourself !

Do you feel confident that you can lead your team to thrive? Do you know your legal responsibilities in relation to providing a safe working environment?

Check out our next virtual workshop - Mental Health for Leaders, Advanced: everything you need to know about Mental Health at work, and tools to help you and your team avoid psychosocial risk, and thrive. Find out more and register here: https://www.theeffect.co.nz/workshops/mental-health-to-lead-advanced-2022

Blog by Ngaire Wallace