A couple of years ago, I tried out for the fire service.

Facing down the entry to a confined-space maze designed to test my response to claustrophobic conditions, I realised that I had spent far too much time focusing on my running speed and pull-up ability and nowhere near enough time practising the mental skills I would need to control my fear response and manage anxiety under stress.

I failed.

Not only did I fail, I developed a bit of anxiety for this particular test. The first time around, I felt fairly calm throughout, but I just wasn’t quick enough. The second time, my pulse raised to the point I felt as though I might pass out as soon as the instructor began to help me into the 20kg+ of fire kit and blacked out face mask I was required to wear.

Failure scares me. Especially when it involves getting stuck in a dark hole.

Artist credit: Sarah Andersen, Sarah’s Scribbles

I made it through, although again, too slowly. The final section of the maze was so constricted, I had my arms pinned to my sides and could only move by pushing myself along with my toes.

“If you get stuck,” the instructors reassured me “we’ll throw a line down and pull you out.”

It was the longest two minutes of my life.

When I eventually managed to toe-wiggle and squeeze my way through, I told them that perhaps this wasn’t the right career choice for me. After all, people would be relying on me to come to their rescue in the most challenging – and potentially, terrifying – situations, and surely they deserved a person who was confident and unafraid.

This dog is my career aspiration.

Artist credit: Meme created by artist K.C. Green as part of the Gunshow comic

“I’ve been a firefighter for 30 years,” the lead instructor told me, “and I’m terrified of heights. I sing to myself while I climb the ladder.”

“I hate confined spaces,” another said. “I froze in one on the training course and had to be dragged out.”

“We’re not looking for people who aren’t afraid. It’s normal to be afraid. It’s how you manage it that matters.”

Since then, I’ve been intrigued by fear - what it is, and how to control it. Military pressing 35kg, lat pulling 60kg, and running 2.4km in 10.30 was easy. Not panicking when blind-folded and stuck inside a tunnel roughly the same size as I am wearing 20kg of gear in 40 degree heat was where the real test began.

The good news is that you don’t need to be prepping to face down burning buildings to benefit from facing your fears or managing anxiety.

Can ordinary people learn to overcome fear?

Fear and Anxiety – what are they, and what’s the difference?

Fear is a biological response to threat present in our immediate environment. Fear helps to keep us alive. Fear is physical.

In response to a perceived threat – the sound of an animal that might harm us, the realisation that we are balancing precariously over a life-endangering height – our amygdala triggers a range of physiological changes to help us survive. Stress hormones cortisol and adrenaline are released. Our breathing and heart rate become rapid. Blood moves from our heart to our limbs making it easier to run fast.

Fear can impair our judgment, because our responses move away from our cerebral cortex (the ‘thinking’ part of the brain) to our limbic system (the ‘emotional’ part of the brain). Physiological changes kick into gear that can hamper our ability to think rationally.

Fear can save our lives. When we are about to slip and fall, or when we almost step on a rattlesnake, an immediate physiological response is what we need.

In order for fear to be helpful, it must correlate to threat level.

Artist Credit: Dharma Comics by Leah Pearlman

Much research has been done on the impact of fear in decision-making – you can read about some of it here.

Anxiety

Anxiety feels like fear, but occurs without an immediate threat.

The thought of a threat, or feeling an emotion relating to a perceived threat, can trigger anxiety.

Artist Credit: Gemma Correll. Follow Gemma on Facebook here

For example, someone who is experiencing a near-miss traffic accident will feel fear as they see an obstacle approaching and slam on the brakes. Their heart will race as they hear and feel their tyres skid. They may feel light-headed and breathless as they come to a sudden stop and notice their hands shake as they put the car back into gear and resume normal driving conditions.

A person experiencing anxiety around driving may feel their heart race as soon as they begin thinking about getting into the driver’s seat. This could escalate to a phobia (fear-symptoms specifically focused around driving), or more generalised anxiety, where a person begins to feel anxious around various aspects of life (including feeling anxious at the prospect of experiencing anxiety).

If symptoms of anxiety begin to interfere with enjoying daily life, then it is time to seek help from a professional.

Psychotherapy is usually recommended as the first step, along with self-care. Proper sleep, eating well and avoiding triggers (such as caffeine) can make a measurable difference.

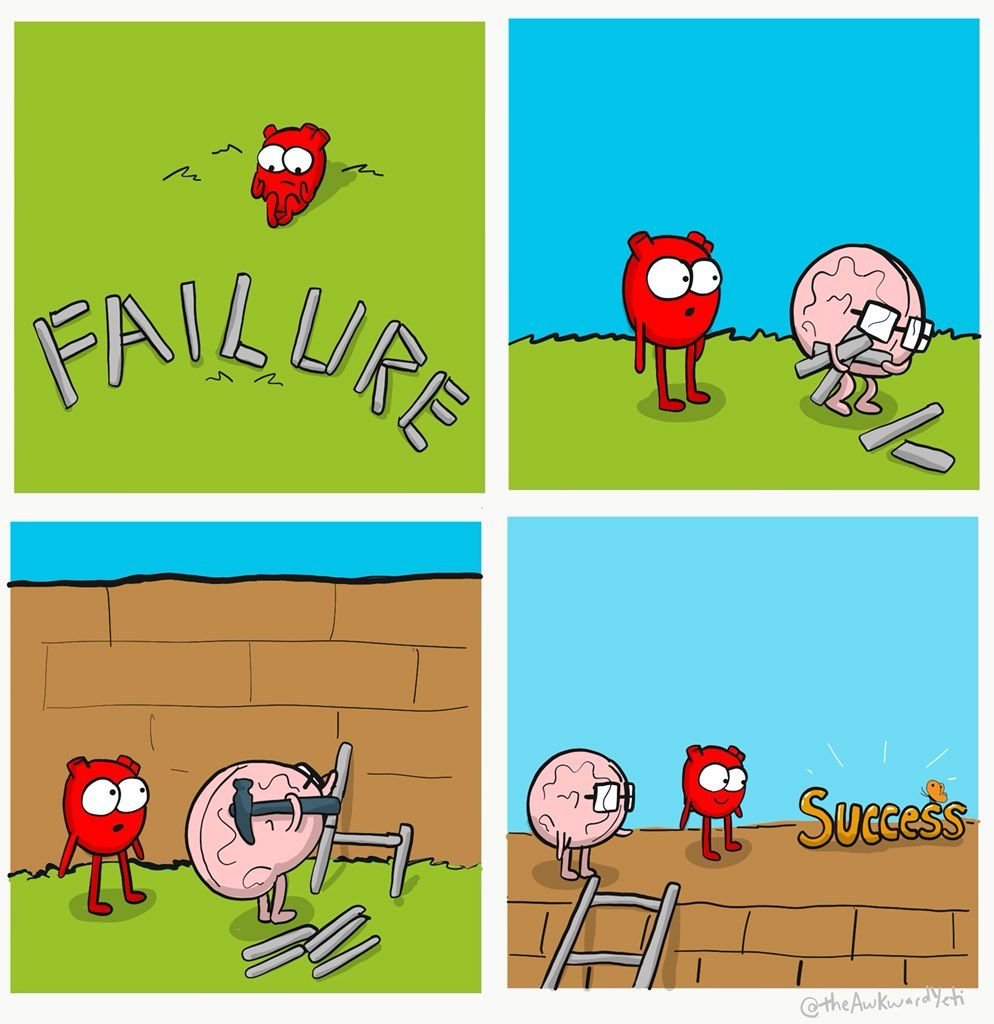

Artist Credit: Nick Seluk, The Awkward Yeti

However there are several simple techniques that anyone can use to assist and manage fear and anxiety.

How to face your fears, and manage anxiety, right now

The Physiological Sigh

Two inhales followed by a long exhale, practised 1-3 times, can dramatically reduce feelings of anxiety.

Sighing is essential for lung function and a natural response to stress. The average human sighs involuntarily once every five minutes.

When we are stressed, our pulse quickens, our blood pressure rises, and our breathing becomes more shallow. These physiological responses can heighten our feelings of anxiety even when a threat isn’t present. If we can calm these physical reactions, we can reduce our feelings of stress. In other words, using the body to calm the mind.

This dog’s threat response is a real vibe.

Artist credit: Jimmy Craig comics, They Can Talk

The double inhale increases the surface area of the lungs, making them work more efficiently, and the long exhale sends a signal to the brain to slow our heart rate.

This simple breathing technique can help to calm two of the main symptoms of anxiety (fast breathing and quickened pulse) within seconds, and can be applied by almost anyone, for free, in virtually any circumstance.

If you are experiencing anxiety, the physiological sigh can reduce symptoms.

If you are experiencing fear – perhaps you are a rock climber focused on moving to the next level, a firefighter with a fear of heights, or a leader with a fear of public speaking – you can use the physiological sigh to calm your fear response. This will enable you to use your rational thinking ability and control your physiological responses even when under extreme stress.

Image Credit: Sarah Andersen, Sarah’s Scribbles

You can learn more about this in this excellent podcast by neuroscience Professor Dr Andrew Huberman.

Graded Exposure Therapy

Mithridates was a Greek ruler and formidable opponent of the Roman Empire, who was so afraid of assassination by poison, he ingested a little daily in a safe quantity in order to develop an immunity. This practice is now called mithridatism, and you can try it to.

Think of it as ‘what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger,’ or ‘the dose makes the poison.’

Identify a tolerable threat level relating to your anxiety trigger.

Afraid of driving in big cities, through large roundabouts? Drive a few blocks around your local area. When that feels fully comfortable, try a medium-sized roundabout, and so on.

Afraid of heights? Book a climbing coach who you fully trust, and try climbing to a challenging but safe level, with guidance and a harness. Gradually stretch yourself. When you begin to feel triggered, practise the physiological sigh to calm your stress response.

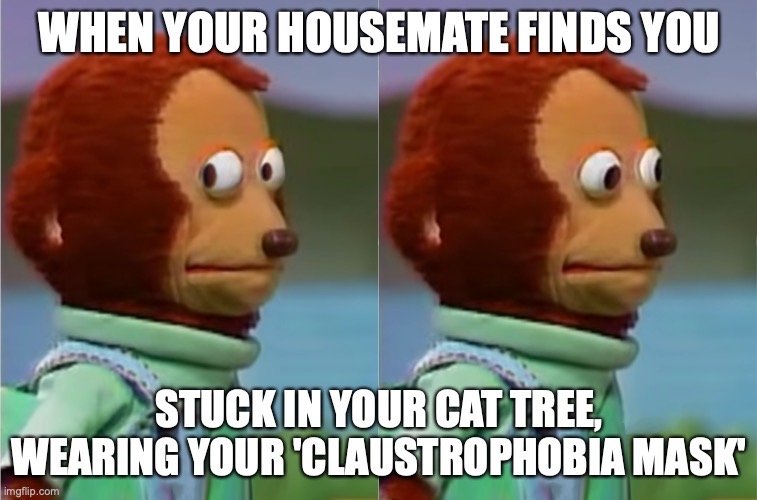

I tried this at home by setting up obstacles, blindfolding myself, and crawling through the house (including our cats’ tunnels), and discovered that it’s not so much the lack of sight that sets off my feeling of panic, but the feeling of having my entire face, head and breathing constricted.

I’ve since set about sourcing a full latex hood for my home claustrophobia trials, which as you might imagine has led me to some unexpected places on the internet. Wish me luck.

Visualisation and mantras

Our brains are clever beasts. We create thinking ‘short-cuts’ or heuristics, that enable us to apply learning from one situation to another that feels similar. When it comes to fear and anxiety, this ability can either be adaptive and helpful, or distinctly unhelpful.

With repeated thoughts, we lay down neural pathways (essentially, thinking habits). Like a well-trodden path, the more our brains walk down familiar paths, the more well-worn those paths get and the more difficult to carve out a new direction.

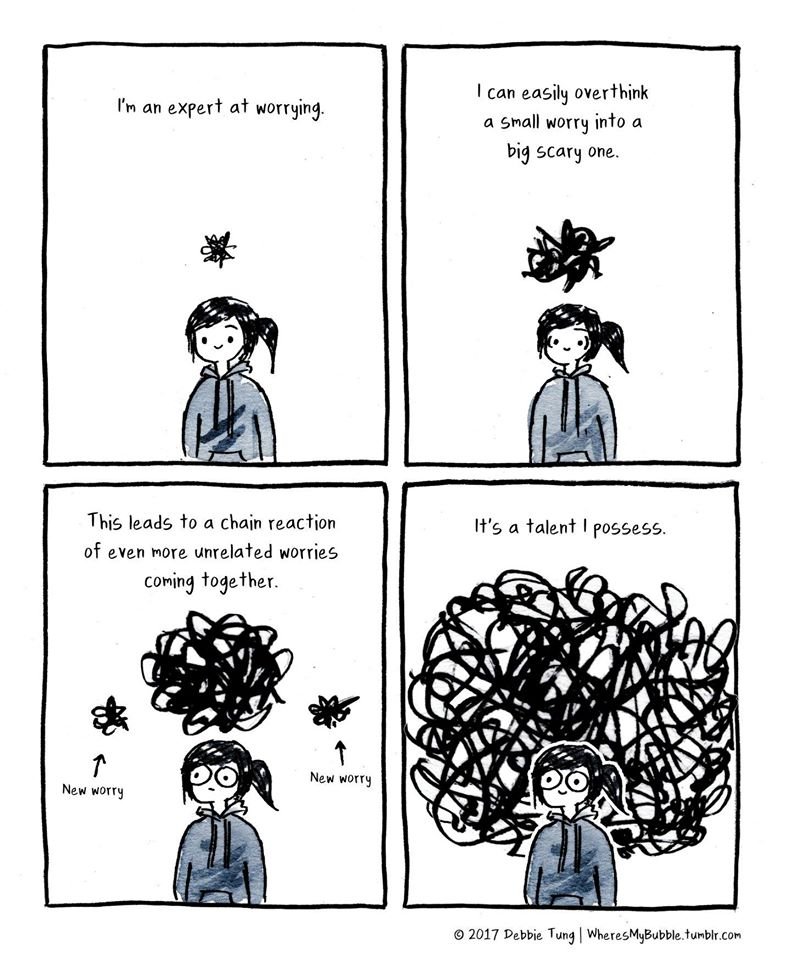

Artist credit: Debbie Tung, Where’s My Bubble

The good news is that you can use this ability to help you, by consciously creating helpful neural pathways.

Rather than repeatedly thinking to myself ‘I failed this test last time, I am afraid of this test’ (or something similar) I can choose to think ‘I am safe. I am cosy. I am comfortable.’

This strategy becomes even more powerful when practised in advance and accompanied with visualisation.

Sports people, business people (and anyone with a challenging goal to reach) have been using visualisation to aid their performance for decades.

Get yourself into a safe place, and then imagine yourself in a challenging situation. Stay relaxed by focusing on mindful breathing.

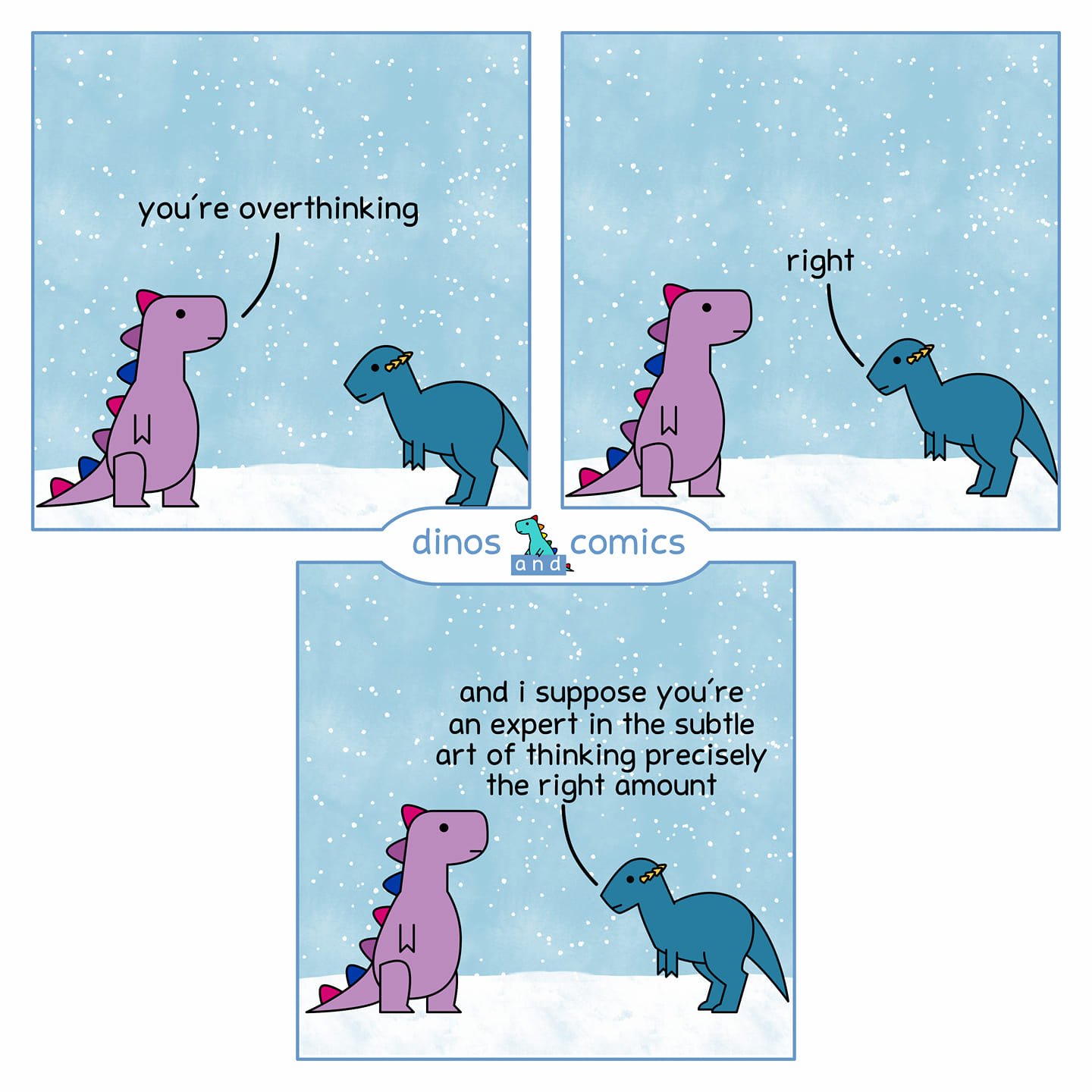

Artist credit: Dinos and Comics

This technique works best with more detail – rather than imagining seeing yourself (like watching a film), imagine that you are actually in the situation. Think step by step about your environment – the sounds, the smells. Make it as real as possible. Then repeat your mantra. ‘I am safe. I am cosy. I am comfortable.’

It’s important to choose a simple phrase that really resonates for you, and practise it frequently, so you really lay down those neural pathways and these helpful thoughts come to you naturally when you need them.

The Rule of Threes

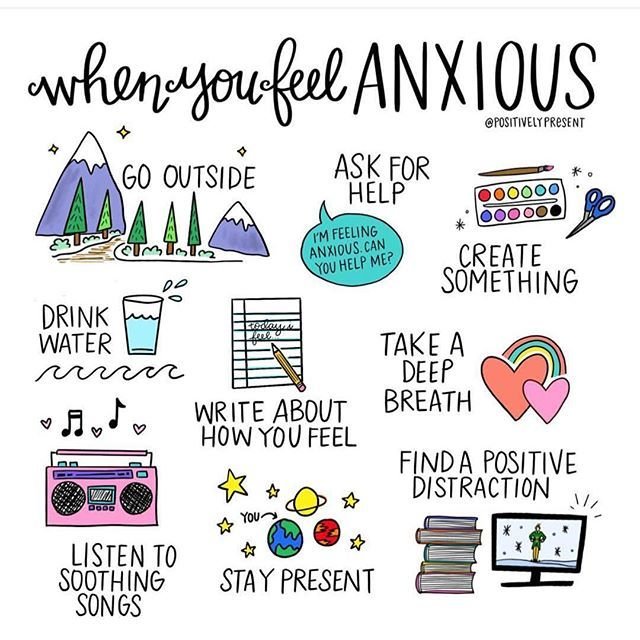

What can you do when you’re in a crisis moment and experiencing anxiety symptoms?

Bring yourself out of your head and back to the present by grounding yourself in your body.

Look round you and name three things you can see. Then three things you can hear. Finally, move three parts of your body. Really focus on the physical attributes and sensations of these movements. This will help you to bring you out of repetitive thought loops and ground you in the present moment.

Add in a few physiological sighs and you will be on the pathway to reducing your symptoms.

Artist credit: Dani DiPirro, Positively Present

Remember, if you or someone you know suffers anxiety; whilst the immediate ‘threat’ may not be real, the debilitating fear-response symptoms absolutely are.

To hear more about the personal experience of anxiety-sufferers, NZ based readers can view this documentary delving into personal perspectives and the neuroscience behind these events.

Conclusion

I'd love to loop back around with a feel-good anecdote relating how I eventually conquered my fears and aced that test. Unfortunately, the thought of putting that blacked-out visor on and crawling into a series of unknown confined-space tunnels still scares the living daylights out of me.

But, I have all the strategies in place to help me succeed. I am working on it.

And so can you.

When all else fails - keep trying.

Artist credit: The Awkward Yeti

***

Blog by Ngaire Wallace - follow me here.

Interested in understanding more about the Psychosocial Risks in your organisation, and how you can reduce stress for you and your team in the workplace? Check out our Psychosocial Risk Assessment service here.

Want to learn more about mental health at work? Click on our events page to view our upcoming virtual workshops - including our upcoming F-Word session all about how you can find your flow and have more fun at work.

We also offer personal coaching, burn-out recovery support and conference speaking - contact us to book.