International Women’s Day 2023 has been and gone but the challenges that women face to experiencing equity in the workplace remain.

What are those challenges, and what would an environment that successfully controls for psychosocial hazards at work that particularly impact women look like?

I attended a fantastic event last weekend run by Bristol Women’s Voice, exploring the challenges that women experience, ways to overcome them and celebrating the strengths of women and girls.

A comment by one of the speakers really stuck with me.

“No amount of street lighting can dismantle the patriarchy.”

The speaker was referring to designing cities and towns in ways that proactively support public safety, but we can apply the same metaphor to psychosocial hazards at work. No amount of policy and procedure will erase misogyny, but that doesn’t mean that workplace policy can’t be used as an effective tool to establish change.

So what can we actually DO to make workplaces more equitable for women?

What is gender equity in the workplace?

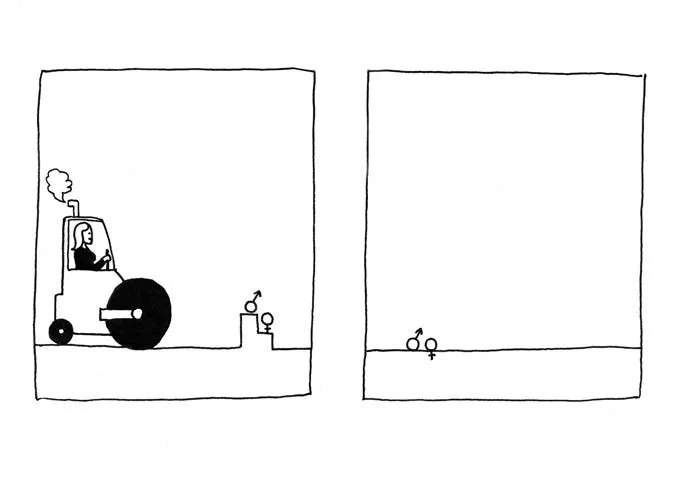

Artist credit: This wonderful image is by Brice Tadé Tangou, aka Ted Ulty, and won the UN Women Generation Equality: Picture It award 2021. He writes ‘#GenerationEquality reminds us of the important value of women’s and girls’ contribution to society when their rights are respected; #GenerationEquality also represents the possibility for everyone to participate in different spheres of society without discriminatory barriers.’

Firstly, let’s be clear that we are not looking to ‘lower the bar’ or ‘box tick’ to achieve more diversity simply for the sake of virtue signalling.

The idea that women, or any other minority group, need to have the bar lowered is in itself, discriminatory. We are not asking for equal outcomes that are not based on equal merit. We are asking for equal opportunities. That doesn’t mean a leg up or a free ticket to the top but rather, removing the barriers that prevent women and other minority groups from having the same chances.

On International Women’s Day, social media is littered with posts thanking and celebrating ‘amazing’ women. Yes - I can name many amazing women who manage to juggle all kinds of complicated work and home responsibilities.

Many of them have privileges such as access to childcare, or partners who help, or they may simply be incredibly resilient.

Women shouldn’t need to be amazing. The path to success should have fewer obstacles on it.

Stop ‘celebrating’ incredible women and start implementing or advocating for policies that enable all kinds of women to access opportunities.

Artist credit: Mariola Stachnik, semi-finalist, UN Women Generation Equality Picture It award 2015.

Psychosocial Hazards in the workplace that impact women

Now that I have that rant out of the way, let’s look at some of the psychosocial hazards that impact women’s mental health at work and one control that employers can implement to manage that hazard - one control to rule them all, if you will. Beware though - used incorrectly, this tool can exacerbate psychosocial hazards in the workplace.

A quick definition of Psychosocial hazards: hazards that arise from poor work design, management, and the social context at work, that can lead to negative psychological outcomes (which in turn can lead to negative physical outcomes).

Not all of these psychosocial hazards impact women disproportionately, but they may impact women in different ways.

Note that all of these psychosocial hazards are exacerbated when they intersect with other forms of exclusion. In other words, the barriers to access are even higher for women of colour, neurodiverse women, women with disabilities and LGBTQ+ women.

Burn-out and overwork

There is a conception that women experience more burn-out than men. The research doesn’t support this. However, women may experience burn-out for different reasons than men. In other words, the pathways to burn-out may be gendered although the frequency appears similar.

The difference here is critical, because if women are incorrectly perceived to be more likely to ‘burn out’ they may be perceived to be less capable of handling stress and then passed over for promotional opportunities.

Conversely, if men are incorrectly presumed to be more resilient, they may either be offered fewer supports or be less likely to take available supports up, resulting in poorer workplace mental health outcomes.

Regardless of individual resilience, research indicates that burn-out is more likely to occur in workers who work over 55 hours per week (Haar, 2021). Research shows that men typically work more paid hours than women, whereas women work more unpaid hours (and including paid work, more hours overall). In Australia, this amounted to an average of 55.4 hours per week for women aged 15-64.

For a meta-analysis of gender and burn-out, see here (Purvanova & Muros, 2010) and here (Beauregard, et al., 2018).

Gender discrimination eg being overlooked (unconsciously or otherwise) for promotional opportunities.

Despite significant progress over the past decades, there are far fewer women than men in senior leadership roles. This isn’t because women aren’t capable leaders but because of systemic barriers that prevent us from having access to these job roles.

Sometimes access really does mean access. Train stations across the UK were granted £20 million in funding to improve accessibility, following pressure from advocacy groups for both passengers with disabilities and parents (usually mothers) with buggies.

Access to one station in Bristol required that passengers traveled backwards for one stop before returning in the opposite direction, if they were traveling with a wheelchair or pram.

In this instance, working mothers and people with disabilities were/are quite literally traveling away from work in order to get there.

Artist credit: Noa Poljak, semi-finalist in the UN Women ‘Generation Equality’ picture-it award 2021 Noa writes ‘To equally succeed, women are expected to thrive more, be more persistent, have more knowledge, more skills and more patience than men. Their career paths and family lives are full of challenges and obstacles; therefore, I want to shine light on a problem that I have witnessed first-hand.’

Incivility / microaggression

I will explore this further in another blog as it’s such a huge topic but for now let’s stick to the incivility that can manifest when women are perceived to be absent from work more frequently than men, OR when it is presumed that they will be, when at some future point they have children.

How many times have you seen someone roll their eyes when an employee announces maternity leave? Or received an email from a working mother at 10pm because she is desperate to not be perceived as shirking, having ‘logged off early’ to do the school-run? Or noticed a woman of around 30 join the company and wondered how long she will stay in the role for before ‘disappearing’ to have children?

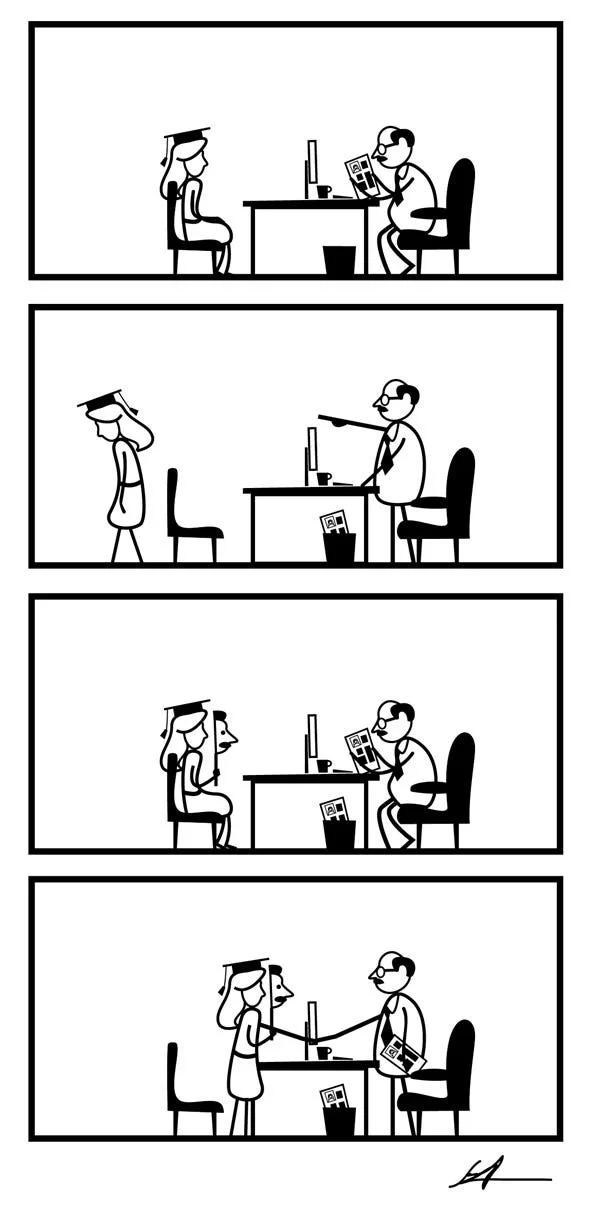

Artist credit: Agata Hop, semi-finalist in the UN Women Generation Equality picture-it award. She writes ‘gender equality means that men and women are able to achieve the same degree of success through an equal effort.’ Side note - the artist produced this comic whilst in high-school.

Poor job control

Multiple studies indicate that women spend more time in unpaid caring than men do, and they spend more time doing housework, regardless of working hours (women who work more than men still spend more time than men, on average, in domestic work). This is not to say that men who do more than their fair share don’t exist - my other half, for example, does significantly more cooking and cleaning than I do, but statistically speaking, we are outliers.

This means that women are less likely to have control over their working hours. They have fewer choices, because they are more likely to need to fit their working time around multiple other commitments. This in turn means they have fewer choices regarding the type of tasks and projects that they accept at work and even the type of position. They may be more likely to take on shift work, and more likely to work in lower paid and highly scripted job roles (call centres for example are significantly dominated by women).

Many employers require iron-clad reliability for some types of job roles, for example positions requiring frequent client contact. They may also unconsciously (or consciously) believe that multiple commitments outside of paid work might reduce women’s cognitive capacity, ability or desire to take on more complex or demanding projects.

All of these can lead to women having less control over the type of work that they do, and more likely to be in positions that feature lower job control.

Artist credit: Samuel Akinfenwa Onwusa, a third place winner in the UN Women Generation Equality Picture It award, 2015. He writes that gender equality is inextricably linked to education, and ‘is a goal that has to be set in the minds of people, especially children, to thrive peace and harmony.’

Research by the Centre for Progressive Policy in the UK showed that women in the UK spend twice as much time as men in unpaid childcare, and also more time than men caring for adults. 45% of women who cared for others say they can take on more hours, while 20% say that they could take on a new role if it were available and 14% said that they would be able to take up a different job.

It is not that women can’t or won’t take up more complex and senior roles in and around their unpaid caring work, it is that society doesn’t allow them to.

Side note - (arguably) less complex and more junior roles should be valued more. Many female-dominated industries such as teaching, nursing and caring are physically, emotionally and cognitively challenging as well as being essential to society, and yet are underpaid.

The picture in Australia is similar, according to the recent status of women report card.

Consider - is it really a character flaw to have to reschedule a client meeting because of a personal commitment? It shouldn’t be. Why don’t we, as a collective, start to support people who can’t, or who don’t want to, prioritise their jobs over their families and relationships? As a society we would be happier and healthier, with more diverse and successful workforces.

OR/and let’s re-design working patterns so that we can ALL have the ability to devote ourselves to both our work and our commitments outside of work.

AND let’s redesign care; so that caring work is valued and supported and shared equitably.

Let’s face it - governments have either run out of money or choose not to spend it equitably. Globally, mental health and social care pots are exhausted. We have to look after each other, in addition to advocating for public services that effectively support social change.

One psychosocial hazard management tool to rule, or exacerbate, them all

Flexible working policies and psychosocial WORKPLACE HAZARD management

Well-meaning, but ineffective flexible working policies, particularly when combined with overwork cultures can hinder women’s advancement at work.

This fascinating article from Harvard Business Review outlines research conducted at a global consulting firm, which showed that both men and women suffered from work/life balance struggles, however only women were encouraged to take up accommodations supposedly designed to help them manage both work and family life, which in fact derailed their careers (such as part-time working hours or switching to internal-facing roles).

The problem holding back women was not the women’s capacity (or lack there-of) to juggle work and home, or their “choice” to take up the accommodations offered to them, but the firm’s culture of over working which made it impossible for all genders to have any kind of life or responsibilities outside of work, and which punished women for trying.

What does good look like?

Flexible working policies should offer genuinely flexible working. Swapping a full-time day in the office for a full-time day at home is not flexible working (although it may be better than no flexibility at all). Flexible working works around the employee and is available to everyone for any reason, in addition to being taken-up equitably by everyone.

If flexible working is offered to everyone, but only women take it up, (perhaps as a consequence of societal expectations around women’s role as carers, or because women tend to be in lower paid job roles therefore more likely to cut back their own hours when needed), then the flexible working policies are likely to hurt women’s career advancement, not help them.

Inequitable flexible working also impacts the ability of men to spend time with their families, develop relationships with their children and has resulting wider societal impacts.

Artist credit: Aitor López García, a third place winner in the 2015 UN Women Generation Equality Picture It award. I loved what Aitor wrote about the meaning of gender equality ‘that one day we won’t need to speak about equality anymore.’

A really good flexible working policy would look like government intervention, requiring mandatory paternity/maternity leave. In the absence of that, employers can consider options such as productivity based working patterns - not requiring specific hours at all, but rather, requiring that tasks be completed and targets be met. Compressed working hours (longer hours, over a shorter time period), or allowing hours to be delivered as available, around other responsibilities.

In addition to this, we need equitable procedures for career advancement, where employees’ performance and potential is considered, rather than their availability for face-to-face engagement with more senior staff.

Providing advancement schemes that include flexible / hybrid workers can help to avoid promotional bias.

For example virtual mentorship programs; scheduling team relationship-building at times and locations that are accessible to everyone and rigorous recruitment methods that actively reduce or eliminate bias.

All of the above requires high levels of effective communication across individuals and team, flexible thinking, diversity education and a willingness to consider outside of the norm approaches.

Equitable working policies that actively include everyone do not only benefit women.

Working practices and promotional behaviours that favour in-office workers also tend to exclude people with disabilities, neurodiverse folk and people of colour, as well as impacting men’s mental health by encouraging over-work and poor work/life balance.

Policies that help women, help everyone.

What else can leaders do to avoid bias against flexible workers?

NORMALISE having a life outside work. Are you a leader who wants to be an ally, to pull people up the ladder behind you? Then make the space at the top wider. Go and pick your kids up at 4pm. Leave a meeting early to attend a school rehearsal. Tell your clients you are not available on that date because you are taking an ageing parent to a hospital appointment. This may seem contrary to commercial business practise but consider how much productive working time and potential for advancement is lost when an individual suffers from burn-out, or isn’t in the job at all because they have been excluded due to factors that aren’t connected to their skills or potential.

Work should be a part of our lives, not completely take over our life. Juggling all these schedules for everyone and making it work might be a major pain in the backside but it will blast your talent pool wide open, and help your organisation’s creativity, organisation and ultimately, success.

Artist credit: Femi Philemon Ogunsanmi, a third place winner in the UN Women Generation Equality Picture It award 2021. He writes ‘Like the battery needs both terminals to function, every sphere of life needs to harness its human resources regardless of their gender, in order to reach maximum productivity.’

You don’t need to lose your organisation’s brightest stars to their responsibilities outside work. Make work work for them instead.

Do you need help to re-design work that supports everyone?

Glia is here for you.

We are a team of highly experienced registered Psychologists who are experts in the world of work.

Contact us for Psychosocial Risk Assessments, Leadership Coaching, and virtual or in-house workshops to support mental health in the workplace and reduce the impact of psychosocial hazards at work.

Follow us on LinkedIn for our regular, and FREE educational LinkedIn Lives with special expert guests covering Psychosocial Risk Management, Workplace Mental Health and compliance.

Follow the writer, Ngaire Wallace, on LinkedIn here.

And one more comic just for fun, to celebrate all the women out there whether they be amazing or plain old mediocre. Go get ‘em.

Artist credit: Jakob Topor, semi-finalist, UN Women Generation Equality Picture-It award 2015.