Content warning: Please be aware that this blog refers to various types of loss and emotions surrounding loss. It may not be suitable for you if you have suffered a loss and/or are feeling sensitive at this time. Please take care when reading.

***

Last week, I lost someone very close to me, and I’m writing a blog about grief because quite honestly, I can’t think about anything else.

Debbie was warm, kind, funny, clever, and gracious. If our years on this planet were handed out according to the amount of joy we brought to those around us, Derbs would have at least another half a dozen decades to go, but sadly that’s not how life works. She died suddenly, aged 32, due to a completely unexpected medical event. She left behind her a wide circle of friends and a family who loved her dearly.

Grief comes to all of us at one point or another, and when it comes, it strikes a hammer blow.

And yet, life goes on. Laundry mounts up, bills land in the post, the dishes need doing, and the recycling collection comes on the same day. It’s a bit like being on a carousel ride where one person has got off but you can’t stop your own horse.

If you’ve seen Four Wedding and a Funeral, you might remember the W.H Auden poem, Stop All the Clocks: (you can see a clip of John Hannah reading it here.

Stop all the clocks, cut off the telephone,

Prevent the dog from barking with a juicy bone,

Silence the pianos and with muffled drum..

It feels as though the world ought to stop, because for the people grieving, a part of the world has stopped. But, it doesn’t stop, and work is one of the things that - sooner or later - most of us need to carry on with.

Artist Credit: Haley Weaver, Haley Drew This

The question is how - how do you work through grief? And if you are an employer, manager or colleague, how can you support grieving members of staff?

The first thing to remember is that everyone copes with grief differently. There’s no cap on feelings of grief and nor is there an expiration date. There is no time line for stages or processing emotions and there’s no right or wrong way to feel.

Some folk might want to go back to work straight away, to create a feeling of structure and routine and to be around people. I am one of those - I work in manufacturing in addition to writing this blog, and whilst my first shift back was hard, the physical movement and familiarity helped to calm my mind and working to a schedule helped to get my sleeping patterns back on track.

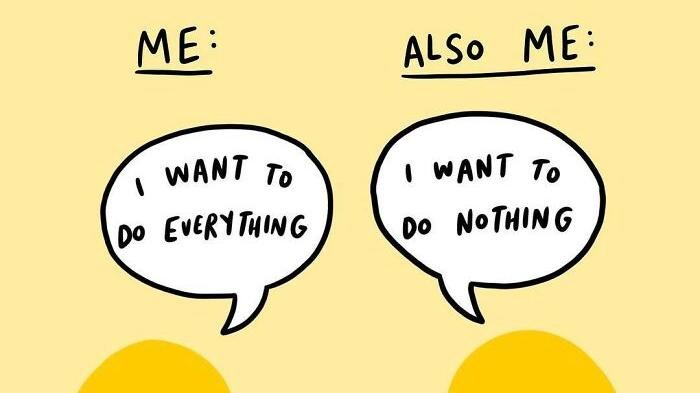

Artist credit: Sarah Andersen

Others may find that they simply can’t work at all, especially if they have a job that requires creativity or putting on an emotional front they simply don’t feel. Motivation may wane, and career goals or project targets that seemed important before fade into insignificance.

So far, I have been capable of executing rote tasks. But, when asked my opinion about something or input into a strategic plan - things that would have previously interested and motivated me - it is only politeness (and an awareness that I do, in fact, need my job) that has prevented me from responding that I could not care any less.

My emotional regulation is up and down. Some days, I can find meaning in loss. I feel that life is brief and precious and that I’ve been given an extremely bitter pill to swallow, one that will in time help me to make the most of the time that I do have. Other days I feel dark, empty, apathetic and irritable. I kick the recycling box into the wall on my way through my front gate.

Grief is inside me like some kind of faceless amoeba that grows and shrinks, expands and contracts, but never goes away. It touches different bits of me at different times and without any warning. I don’t expect that it will ever go away, and I’m not sure that I want it to.

Artist credit: The concept behind this image is based Dr Lois Tonkin’s model ‘growing around grief’ - the idea that grief stays the same, and our lives evolve around it. The image was developed by the Ralph Site, a website dedicated to pet loss.

I think of her virtually every minute of every day. Sometimes these thoughts are quiet little memories peeking up in the background that don’t interfere too much with the present; and other times, the smallest things set off a crash of emotion that breaks over me like a wave.

The other day I was cycling home from the gym and saw a pile of leaves on the ground that made me cry, because she loved Halloween and hated too much sun, so the arrival of autumn in the UK reminded me of her. I’m really not an openly emotional person, so all of this has been surprising and weird. Grief has cracked me open like an egg.

Artist credit: Fun Fact Comics @funfactcomics

My sleep has been up and down. I wake up suddenly at 2.30am with that jolted feeling you have when you dream of falling. I am simultaneously exhausted and restless. I am eating, but less than usual and mostly soup. My attention span is shot to bits. I got out of the shower and put SPF 50 sunscreen onto my face rather than moisturiser. I put the laundry out, then 20 minutes later opened the washing machine, confused at finding it empty. I wandered the house looking for a pile of wet clothes only to find I had hung them out already.

What does all of this mean for my job? Well, if I were in charge of me, I wouldn’t put me in charge of a forklift, an important financial plan, heading a client meeting.

I was ten minutes late (unusual for me) on my first day back, because my car wouldn’t start so I’d had to take my husband’s. It turned out I just had the steering lock on. I’m not my usual self, and I need some empathy. I have made small mistakes, I’m quieter than usual, sometimes I’m grumpy. Sometimes I need to stand outside for a minute and catch my breath. Mostly, I work like a demon, just to quiet my mind.

Artist credit: Dinos and comics @dinosandcomics

Tips for employers / managers / leaders (when a staff member is grieving)

We live in a ‘positivity culture’ that prioritises happiness and ‘soldiering on.’ Most organisations espouse values that are in line with positive psychology - striving for team co-operation, motivation, engagement, enthusiasm and gratitude.

Research has shown that tapping into these types of feelings does have a positive impact on worker satisfaction, and using tools that encourage our brains to look on the brighter side reduces stress.

But, life is not all roses, and a crucial part of leadership and of building a company culture that actually feels genuine and not just a bunch of platitudes is offering support to employees during the more difficult times of life and not just the good times.

Artist credit: Nathan W Pyle @nathanwpyle

Consider your bereavement policy, and whatever it is, make it easy to find.

Death requires an awful lot of administration. There are decisions to make, sandwich flavourings to choose, call-centres to phone, music to pick, people to tell and accounts to settle. The bereaved must face (and in many cases support) the grief of others and others’ response to grief.

The last thing that person needs is to be wondering how much paid time off they are entitled to and if they need to make a choice between being flat broke or coming back to work sooner than they feel able to and ‘powering through.’ Even if you have a policy readily available on your intranet, just get in touch with the grieving person and let them know what it is. It will save that person the mental energy required to click through policies or find and trawl through an employment contract.

I worked in recruitment and HR for many years, and 3-4 days was a common bereavement entitlement. This is barely enough time to recover from a toothache. The bereaved person may never be back to ‘normal’. Their resilience to stress will likely be lower than usual, their focus may suffer and they may feel an array of emotions that make productivity difficult. They might need a gradiated return to more complex tasks. On the other hand, they might want (and be perfectly capable of) more work. Trust that they know what they need and give it to them.

Artist credit: Brian Russell, The Underfold

If you are a small business with a limited budget, or you are in a managerial position in a large company without decision making power over paid leave entitlement, you may not be able to offer the bereaved person as many paid leave days as you would like to, but you can still offer them empathy. They might need to take an hour out and go for a walk. Perhaps they need frequent breaks during the day just to stand outside and breathe for a minute. They may need help with a project, a deadline extension, time to make or take a personal phonecall. If you are not sure what they need - ask them. Set up regular check-ins, not just in the days after the bereavement but in the months to follow. They might need time off for meaningful dates, anniversaries or family events and to support others.

Leading with compassion starts before your team members need it. Take the time to think now about how you will approach these situations and how you can build a culture of compassion within your organisation. Include information about the impacts of grief and trauma within your mental health and safety guidance.

Artist credit: Dinos and Comics @dinosandcomics

Not all grief is visible and not all grief involves death

Last week was baby loss awareness week (9-15 October). Miscarriage is a relatively common occurence, and those who suffer this acute pain may not make it public to others. Fertility issues bring their own feelings of grief.

Some people who are private about their emotions may not reveal that they have lost a loved one.

Other forms of grief can include the loss of a beloved pet, a loss of health, the decline of a loved one through terminal or other illness. There is the loss of a home, the loss of a relationship, the loss of ability following a change in health status and the loss of a sense of ‘old-self’ following trauma. There is collective grief that can occur in a population when a trauma occurs publicly (such as the grief for black communities following the murder of George Floyd).

Learn to recognise the signs of grief (and indeed, any mental health issues), so that you can recognise these in your team and support them when they need it. Build a company culture where emotions are recognised and supported. You don’t need to be a psychologist to be a good leader, but you do need to demonstrate humanity. There should not need to be a business case for being human, but you can be sure that if you offer your team compassion they will not forget it.

Artist credit: The Awkward Yeti,

Grief (and indeed, any kind of trauma) can spread.

Be aware that colleagues of the bereaved person will be feeling their own array of emotions. This could vary from memory of their own losses, to confusion or guilt over how to support the bereaved person. The wider team may need check-ins and support also.

Grief will come to us all, at some point or other.

We have programs for a variety of life stages from school leavers, to graduates, new parents, new puppy owners, working parents, pregnancy/surrogacy/adoption, menopause and retirement. Just like all of these things - even more so, because it is one that will effect all of us) - grief is an inevitable part of life that will impact our work at some point. We are working later in life as pension ages increase and treatments for illness improve. Covid-19 has resulted in an increase in deaths globally (and very publicly). Now is the time to re-consider what policies and support your organisation provides for bereavement and if these are fit for purpose.

Grief is a deeply personal experience and entrenched in culture. There is no one way to grieve.

People of different backgrounds, cultures and religious beliefs will express grief in different ways and may need different support. Don’t presume what the person’s beliefs or needs are, and don’t offer them support that doesn’t resonate (‘I will keep you in my prayers’ is not likely to be much help to an atheist). Consider diversity when you prepare your bereavement policy and if you are not sure how to do this, seek professional help.

Artist credit: Liz Climo @Lizclimo FYI Liz is one of the animators on the Simpsons.

Relationships can be complicated. Don’t make presumptions.

Family stopped being mum, dad, 2.5 kids, a labrador and a white picket fence a few decades ago. Maybe it was never that, outside (heteronormative, predominantly white) early-evening TV sitcoms. The legal status of a relationship doesn’t define depth of feeling. On the other side of the coin, there’s no guarantee that the bereaved person had a positive relationship with the person they lost. I don’t have a single negative memory of Debbie but this is far from true for many people. Grief can bring up positive memories but it can also lead past trauma and anger to resurface.

Whatever the bereaved person is feeling, accept it. Don’t tell them how to feel. There is no obligation for anyone to grieve the death of a family member who caused them pain, and there is nothing to stop a person feeling immense grief for someone who is not an immediate family member.

Tips for colleagues and friends of the bereaved

Acknowledge the elephant in the room

Let’s be honest - most people find emotions - the big stuff - difficult to deal with. Tough emotions are difficult to deal with. Thats why Psychologists go through years of training followed by regular supervision. And it’s one reason we don’t have enough of them. It’s a tough job.

Lots of people have reached out to me in the wake of Debbie’s passing to check in or just to say that they’re there if I need it. They often preface what they say with ‘I know nothing I can say will help’ or ‘I don’t know what to say’. Of course, this may be true. Unless they happen to own a working DeLorean there’s absolutely nothing they can do but every expression of support has been meaningful and welcome.

I know it’s hard. I’ve been the person on the other side wondering what the hell to say. I’ve been the person who hasn’t said anything at all (something I now deeply regret). Just say something. ‘I’m sorry for your loss.’ ‘How are you doing?’ ‘I’m thinking of you’ are all perfectly fine responses and all better than trying to pretend the grief doesn’t exist.

Artist credit: Mitra Farmand

Let the bereaved person talk, and listen. Or let them be silent, and just be.

Emotions can be awkward, and it’s normal to feel the desire to want to ‘help’ or fill in spaces in the conversation with ‘have you tried meditation’ or similar suggestions. If you don’t know what to say, just say ‘I’m so sorry. I don’t know what to say.’ Now is probably not a good time to suggest a juice cleanse or taking up jogging.

Artist credit: Sarah Andersen @sarahandersen

Try this instead.

Image credit: Steve Ogden, @steveogdenart

Take care of yourself too

Supporting a grieving person brings its own trauma. Make sure you check-in with yourself, and don’t give so much that you completely empty your own batteries. Eat, sleep, seek support for yourself if you need it. If you feel grief out of empathy - even if you didn’t know the person who passed at all, or you didn’t know them well - that’s okay. There’s space in the world for your grief too.

Remember the value of the little things

A family friend turned up at Debbie’s parents house very briefly, gave out a few hugs, brought in and folded the washing that was on the line, did the dishes, dropped off a pot of soup and left. That was one of the kindest things I have witnessed. My mum and sister sent us some frozen meals. A friend left a care package on our doorstep consisting of potato waffles and Heinz baked beans (trad UK comfort food). Another friend has been texting me pictures of sunsets and sunrises every few days. Someone I don’t know well at all caught me up in a car park and gave me a hug and an offer of tea and a chat. My brother sent me pineapple lumps from New Zealand. My manager gave me annual leave on the busiest day of the year. I could fill multiple pages with the kindnesses we have received over the past couple of weeks. All these small gestures have meant the world. Don’t underestimate how much a small kindness means to someone.

Artist credit: Chuck Draws Things

Tips for the bereaved

I don’t feel like I can do any justice to this emotion in my writing. I am sorry for your loss, and I am sorry if my words do not resonate with your experience.

These are some things that have helped me, and some things that psychologists recommend. To call these things ‘tips’ seems to trivialise the whole experience but right now I can’t think of a better word.

There is no balm for grief, no magic potion and no tonic that can make it disappear, but there are things that can bring some comfort even for a few moments, and there are some things that can help to prevent grief from spiralling to the point that you can’t function at all for an extended period.

Give yourself food, water and rest

Use whatever tricks you need to achieve this. Whether you set an alarm to eat, can only stomach soup and toast or have everything delivered because you can’t face the shops. If you can’t sleep through the night, try to have a catch-up nap on the weekend. Try anything. Think of yourself as a pet or a plant or child and just do whatever you need to do to meet your physical needs.

Artist credit: Just Peachy comic by Holly Chisholm, @justpeachy on Insta

Connect with others

Whether it be online support groups, grief counselling, or sharing your feelings with friends, don’t try to battle through it alone. If bottling your feelings up actually worked then we wouldn’t have a mental health crisis and I’d be out of a job. If you can’t bring yourself to talk about it or you can’t find the words, you may still find some comfort in ‘being’ with others.

Artist credit: Hey Bob Guy Insta @HeyBobGuy Facebook

Give yourself time to grieve

Bereavement is busy. In between visitors, phone calls, organising and arranging things and going to work, it’s hard to find any stillness in which to actually feel what’s going on inside. But it’s in there, and sooner or later, those feelings are going to come out. If you have a busy life, and moments to yourself a few and far between, try setting aside time. Get up 15 minutes earlier and just be alone with your thoughts. Tell your manager (or your team, if you are the manager) that you need to take a walk at lunchtime. Sit in your car, parked, for five minutes and just be.

Make a plan for the bad days

I know the bad days are coming, and they will probably come when the initial rush has subsided. When the service has finished, the cards have stopped arriving in the post and all of her things have been distributed or taken to charity - when there’s nothing left to organise - we will be left with life as it was before, only without her in it. That’s when I expect the bad days will come.

When they do, I’ll do the things I always do when I have a bad day. Comfy clothes, messages to friends, cheesy films, poetry, art, music. I’m a child of the 80’s, so this includes stuff like Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, the Breakfast Club, Rocky (4 for me), Dirty Dancing, Die Hard. David Bowie and Fleetwood Mac are on repeat and I avoid listening to the Smiths. For poetry I turn first to Mary Oliver, but I also love Hone Tuwhare. I walk the line of poignant and comforting but not too sad. Make a list before the bad days come and when they arrive, get yourself to a safe place and work through your list.

This is from ‘Dancing at the Pity Party', a graphic memoir on grief by Tyler Feder. Most of these resonated with me, and you can read more about Tyler’s memoir here.

Try to avoid (or at least moderate) alcohol consumption, take a walk. Remember that all things pass. The sun rises and sets and the leaves change colour, tides come in and go out, and bad days never last forever.

Artist credit: Fun Fact Comics @funfactcomics

Look for meaning, wherever you can find it

You have most likely come across the ‘five stages of grief’ model devised by psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, who proposed that individuals would experience (not necessarily in a linear fashion) denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. To this list, David Kessler, who collaborated with Kübler-Ross before her death has, with the permission of her family, added a sixth stage - meaning.

Kessler states “It’s not about finding meaning in the death – there is no meaning there. What it’s about is finding meaning in the dead person’s life, in how knowing them shaped us, maybe in how the way they died can help us to make the world safer for others.”

Grief can be a terrible and lonely emotion that brings pain verging on the intolerable. But light can be found in the darkest places, and from any trauma can come growth. We would never swap it for the person or the thing lost, but it may show us how we can help others, or how we can live our own lives better. From this, healing comes.

Artist credit: Jangandfox https://jangandfoxstudio.com

If you’ve read this far, thank you, and I hope that something in this blog gives you hope or comfort, or makes you feel less alone.

Maybe you’re wondering about the title. ‘Grief is like a backpack’ is something our neighbour and friend said to my husband (Debbie’s brother). She described her grief over losing a family member as being always with her, but heavier at some times than others.

My grief will always be there, like a shadow friend and foe that I will forever need to make room for.

And that’s ok. We’ll be ok.

This is Debbie, with blue hair and a hedgehog. Among other things, she loved animals, dark humour, and comics.

Photographer unknown.

Blog by Ngaire Wallace - follow me on LinkedIn here

Contact me directly on ngaire@theeffect.co.nz (please forgive delays in reply as I work part time and am based in the UK)

Contact The Effect team on team@theeffect.co.nz

RESOURCES (please note this is not an exhaustive list, but a starting point for further services).

A list of NZ-accessible grief support groups and networks can be found here

A list of UK-accessible grief support groups and networks can be found here

The website Modern Loss contains a diverse collection of essays, articles and resources addressing varying types of loss. Please note this page is candid and contains humour - start with the About section here to check this is the right tone for you right now.

The Ralph Site is an online, not for profit resource and support group for pet loss.

Please reach out to somebody if you need help.