On my wedding day, I melted a TV with an iron.

I had failed to let my hair and makeup artist know that the four-plug extension lead to which she connected her curling tongs was also powering the iron. The iron was switched off at the extension lead’s plug socket but not the device itself and was resting on top of our AirBnB’s televison. A few minutes after she flicked the lead on at the wall, her tongs came to life, and the telly began to burn.

It was a stressful - though not catastrophic - moment, only a couple of hours before the service. My partner (now husband), rushed to downtown Dubrovnik to search for a new iron, and I sat at home trying to reassure the mortified beautician (using very poor Croatian) that it wasn’t her fault whilst she did her best to finish my hairstyle amid the stench of burning plastic and a haze of acrid smoke.

My groom made it back in time with a new iron, and the rest of the day went without a hitch. That’s if you don’t count the large swell rocking us back and forward that meant I had to stand like John Wayne during the service (we wedded onboard a boat), or the large volume of 5-euro mojitos I consumed from a takeaway bar thereafter, which ended in the worst hangover of my life). Our vows might have read “I forgive you your crinkled shirt, as you forgive me my occasional ill-timed binge drinking, and total ineptitude with electronics.”

Yes, this is me directly after our wedding.

We confessed to the AirBnB owner, paid far too much to upgrade the melted television and still managed to secure a 5-star guest review despite checking out a half hour late because a certain someone was physically incapable of getting out of bed.

I’ve experienced far greater setbacks in life – personally, professionally and financially - but I normally pay people to listen those. Nonetheless, it was a stressful moment, that *could* have gone a lot worse.

This was going to be a blog about recovering from failure. It’s the sort of thing that crops up all the time in motivational speeches and memes – we have all heard about famous entrepreneurs who faced bankruptcy and recovered, athletes and movie stars on a comeback (Mickey Rourke, I’m looking at you), inventors who achieved their genius by first failing 10,000 times.

Failure, according to the internet, is something that successful people must deal with regularly.

Image credit - Me, actually. I just bought a Samsung notebook to practice digital art. I’m hoping these early attempts are good enough to be recognisable and bad enough to avoid libel charges.

When I stopped to think about it though, I couldn’t recall many of the downers in my professional or personal life that I would consider ‘failure’. And I’m not blowing my own trumpet here. I’ve cocked up my fair share of times.

I’ve delivered presentations that felt a bit flat, been challenged in client meetings, had to handle conflict with co-workers, sent emails to the wrong people, forgotten to do crucial things.

None of these things really felt like failure, more like mistakes, bad luck or bad decisions.

Image credit: Extra Fabulous Comics https://extrafabulouscomics.com

The days or weeks where I’ve felt the flattest and really had to dig deep into my resilience stores to get sh*t done haven’t been the result of failure.

They’ve been more like Lemony Snickett’s ‘Series of Unfortunate Events’. A client cancelling at the last minute; or a lost sale on the last day of the month; opening the fridge to find there’s no milk or the coffee jar is empty; rushing to the train station after work to see your ride setting off into the distance, and with it your dream of getting home early enough to ignore the laundry, cook something your doctor would disapprove of, and binge watch a few episodes of Cobra Kai with your cat.

Wait, you didn’t quit your job to be with me yet?

This week, my bike was stolen and a few days later my paddleboard burst whilst I was inflating it (imagine a six-foot balloon going boom in your face whilst you’re blowing it up).

Then, whilst writing this article, I put my laptop down to take a break and go to the gym when I discovered that one of my cats had peed all over my gym bag, containing my favourite lifting shoes (Star Wars Converse, if you must know) and resistance bands.

I had just finished cleaning the wee up when one of my other cats puked up on the rug.

By the time I had finished mopping up the wee and puke, I’d lost half an hour, felt bummed by the thought of doing leg day without my usual squat shoes and warm-up kit, and was ready to pack it all in and spend the rest of the day sanitising my house (top tip – if you hate housework and put it off, find something else to procrastinate and it will be done in no time).

Image Credit @SarahAndersen https://sarahcandersen.com

The irony of all this while writing a blog on recovering from setbacks was not lost on me.

Well, I work for a team of Psychologists, so I turned to them to ask for advice on how to handle this sort of thing. Here’s what I learned.

The Three P’s

Psychologist Martin Seligman; one of the pioneers of positive psychology, studied the different ways in which people are overwhelmed by or recover from setbacks and identified three aspects that can hinder recovery.

Personalization – the belief that our setbacks are our fault. “The cat peed on my shoes because I didn’t put my shoes away. This is all my fault.”

Pervasiveness – the belief that setbacks will impact every area of our life. “The cat peed on my shoes. I am upset and I will be upset all day, I won’t be able to workout at the gym or concentrate at work and I will be unable to focus on my family later.”

Permanence – the belief that turmoil caused by setbacks will impact us forever. “The cat peed on my shoes, now I will miss leg day and I have no other time this week to train. This will throw out my whole schedule. I am never going to get stronger.”

In the moment, it’s easy to blame ourselves (or others) for things that go wrong in life, to imagine that the problem we are facing will impact multiple parts of our life and to hypothesize that the results will go on and on. But it doesn’t have to be this way. We can practise new thoughts.

The cat peed on my shoes because that’s what cats do.

I will be a little late for my workout, but I can wear different shoes. I will feel better after exercise and then I can focus on work in the afternoon and I will be in a better mood this evening.

This was a bad week, but next week will be better.

Artist credit: "@theycantalk https://theycantalk.com

Psychologists refer to this kind of thinking as ‘re-framing’; essentially, looking at something in a different light. This takes a bit of practice. Think of resilience as a type of mental fitness. You can exercise to strengthen your resilience muscle, just like you can do bicep curls for your guns.

One exercise is to take a step back and consider the thoughts behind your feelings. Imagine your negative thought cycle as being a bit like a queue of falling dominos. You just need to disrupt one domino to stop the rest falling. Recognising that we hold a negative thought can be enough to disrupt the cycle of negative self-belief.

Image credit - @Theawkwardyeti theawkwardyeti.com

Where do these thoughts come from?

Humans are biased creatures. We are wired (or at least, socialised) with culturally ingrained belief systems. This set of cognitive biases helps us to make decisions quickly based on a set of heuristics (mental short-cuts) that we learn from our environment and experience. In the moment, our biases feel rational, but they can be unhelpful, and it is possible to learn a new set of mental shortcuts that lead to more beneficial outcomes.

Consistency Bias (Sadler & Woody, 2003), indicates that people tend to judge their behaviour against a set of general self-images. People who believe themselves to be successful will examine their behaviour looking for proof that this belief is true. Conversely, people who hold negative self-beliefs will examine their behaviour looking for the failures that they expect. Think you’re bad at public speaking? You will likely scan your last presentation, looking for faults.

The Just World fallacy (Melvin Lerner 1977, 1980) is the cognitive bias that people ‘get what they deserve’ and theorizes that people tend to associate bad outcomes with negative self-beliefs, which in turn engender further negative outcomes. In other words, humans tend to be orderly, and we look for reasons why things go wrong. When bad things happen, we tend to blame them on ourselves, and then, look for more things to go wrong.

It’s possible that I have experienced failures but I don’t usually see them as such, because I tend to have positive self-beliefs.

Actual footage of me re-scanning my entire life for failures I might have missed the first time around. Well, this was a bad idea.

The techniques that I have detailed so far have been largely based around positive psychology. Much as the name suggests, positive psychology is rooted in optimism.

Having a positive outlook has benefits, but this does not mean that we should dismiss negative emotions entirely.

When positive psychology veers into toxic positivity.

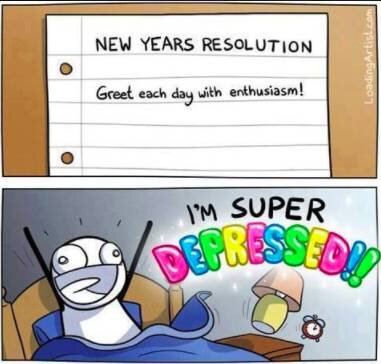

Artist credit: @loadingartist.com

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy.

In a nutshell, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy says that life is shit sometimes, and that’s ok.

The trick is to avoid getting stuck in these moments and overwhelmed by our negative thoughts.

Imagine life as a river, ebbing and flowing over setbacks like water flows over driftwood and stones. It is inevitable that we will experience tough times in our lives. Sit with your feelings, allow yourself to be mad or sad about things that have gone wrong and let those feelings pass. Remember the three P’s (I know, who would have thought there’d be so much P in one blog?)

Artist credit: also me. I apologise it’s little ropey - hopefully I’ll improve with practice.

Taking some time off after experiencing setbacks is a perfectly valid and healthy thing to do. “Getting on with it” might be necessary at times (unfortunately, we do not always have the luxury of taking time out in the moment) but bottling up difficult emotions can lead to greater problems down the line including risk of anxiety, depression and burnout.

If you are a leader, consider offering ‘mental health days’ to your team and normalise taking time off to process difficult emotions. If you are self-employed or have a flexible work-schedule, build mental recovery time into your schedule.

Image credit: Gary Larson, The Far Side https://www.thefarside.com

In addition to beating bias and practicing positive self-talk, taking time for mental recovery is part of building our general resilience.

When considering your own and others’ resilience stores, be generous. Our resilience will vary at different times in our lives. The more we can normalise dealing with struggle, the more people will feel able to seek support to cope with tough times.

We can be strong, and vulnerable.

Make sure your emotional house is strong.

In the Te Whare Tapa Whā model of mental health, pioneered by Sir Mason Durie, the whare (house) is made strong by four dimensions – mental and emotional health (taha hinengaro), spiritual health (taha wairua), physical health (taha tinana) and taha whānau (family) health. Each of these dimensions must be present and strong in order for an individual’s hauora (well-being) to withstand challenges. Connection with the whenua (land) forms the foundation.

Image credit: allright.org.nz https://www.allright.org.nz

We wouldn’t expect to build the walls of our house, live in it all summer and then quickly chuck the roof on when it starts to rain, hoping we manage to get it up in time. Neither would we leave a gaping hole in the wall, thinking it will be fine until tornado season.

Work on strengthening your whare all year round, and then when setbacks come, you will be ready.

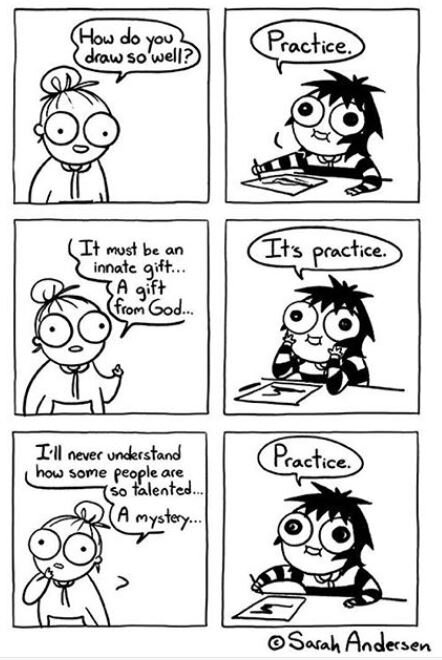

Like anything else in life, to become skills, and to become habits, these techniques require regular practice.

Image credit - @SarahAndersen https://sarahcandersen.com

Building resilience isn’t a marathon, or a sprint. Think of it as a daily walking routine for your brain. When the weather is bad, you might not feel like pulling yourself out of bed and putting your shoes on. There’s beauty (and discomfort) in every season. Committing to a ‘resilience stroll’ most days will help you build a strong resilience muscle, and your mental health will thank you for it.

Want more tips and tricks for you or your team?

Check out our upcoming workshops – Resilience to Thrive on September 8th and Mental Health for Leaders Wednesday 17th November (both Hamilton, NZ).

Not ready to commit to an event yet? Join the conversation on Facebook and LinkedIn.

Interested in our online workshops, coming soon? Sign up to our newsletter here.

Blog by Ngaire – Follow me on LinkedIn here.

Addendum:

There’s two major factors that help in dealing with setbacks which often aren’t addressed in these types of blogs, and those are time and money.

Our problem with the melted TV and iron was resolved because we could afford to replace both at short notice, and part of the reason that I didn’t have a meltdown (pardon the pun) is because I knew I wasn’t about to be evicted from our accommodation with a bad review and nowhere else to go. My cat peeing on my shoes wasn’t a deal breaker, because I own multiple pairs of shoes. I also have a flexible job that enables me to change my schedule if I need to.

My self-belief systems tend to be high because I grew up in a stable, loving environment (thanks, Mum and Dad) with access to healthcare and education, and when I screwed up I was given plenty of second chances. I don’t tend to feel like life is out to get me, because usually, it isn’t.

This isn’t true for everyone.

Resilience is a factor in coping with setbacks. But not the only factor. Our economic situation and degree of privilege play a major role.

Have a think about those lists of ‘famous people who failed’ that are all over the internet. Yes, these sorts of stories can be great examples of the human capacity for perseverance. But they also tell us who we give second (and third, and fourth, and fifth) chances to.

Yes, Edison invented 10,000 ways how not to make a light bulb. But he was also given 10,001 opportunities to try.

Image credit: Charlie Mackesy https://www.charliemackesy.com